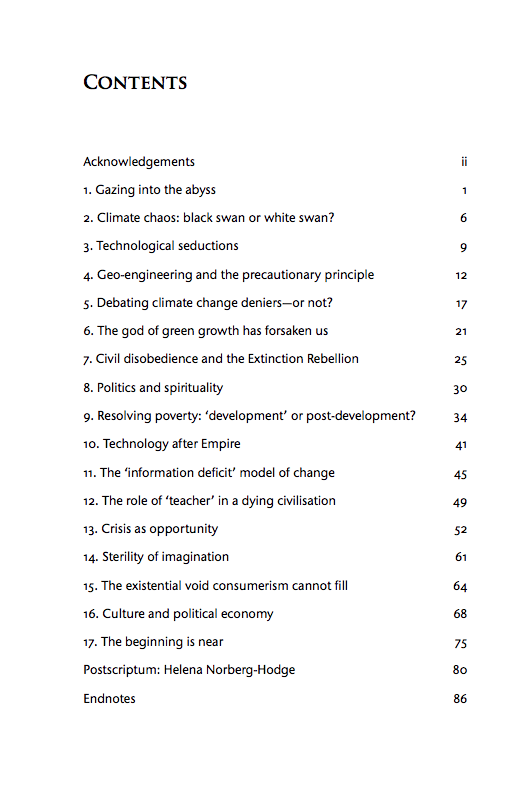

This Civilisation is Finished: Conversations on the end of Empire – and what lies beyond

I’ve just published a new book, co-authored with philosopher-activist Rupert Read (leading spokesperson of the Extinction Rebellion in the UK). There is also a postscript by Helena Norberg-Hodge, author of Ancient Futures and producer of The Economics of Happiness.

Our new book is entitled This Civilisation is Finished: Conversations on the end of Empire – and what lies beyond, but don’t be put off by the title. The content isn’t as gloomy as the title might suggest, although the book is made up of 17 conversations between Rupert and myself on a range of challenging global issues. Readers of this blog and my other books will be familiar with many of the themes, but the conversational style of this book makes it particularly accessible I feel. I hope you are stimulated and enriched by the discussion.

I’ve posted the cover and contents page below, followed by the first of our conversations. The paperback is available here and the e-book is available on a ‘pay what you want’ basis here. Please share news of this publication with others.

GAZING INTO THE ABYSS

Samuel Alexander (SA): Rupert, I would like to invite you into a space of uncompromised honesty. Let us engage each other in conversation, not primarily as scholars wanting to defend a theory, or as politicians seeking to win votes or advance a public policy agenda, or even as activists fighting for a cause, but instead, just as human beings trying to understand, as clearly as possible, our situation and condition at this turbulent moment in history.

When I look at the world today, I see the vast majority of academics, scientists, activists, and politicians ‘self-censoring’ their own work and ideas, in order to share views that are socially, politically, or even personally palatable. There are times, of course – often there are times – when we must be pragmatic in our modes of communication, and shape the expression of our ideas in ways that are psychologically digestible, compassionate, or even crafted to be attractive to an intended audience. But the more we do that, the more constrained we are from saying what we really think; the less able we are to look unflinchingly at the state of things and describe what we see, no matter what we find. If we never find ourselves in spaces of unconstrained openness, we might not even know what we really think, hiding truths even from ourselves.

It seems to me that one of the first principles of intellectual integrity is not to hide from truths, however ugly or challenging they may be. Yet there are truths today which I feel many people are choosing to ignore, not because they do not see them or understand them, but because they do not want to see or understand them. Truth, as any philosopher knows, is a contested term. But perhaps in what is increasingly called a ‘post-truth’ age, time is ripe to reclaim this nebulous notion, to try to pin it down, not in theory but in practice. That is to say, I am inviting you, Rupert, to practise truthfulness with me, to share thoughts on what we really think, and to do so, as far as possible, without filtering our perspectives to make them appear anything other than what they are. This may require some bravery, of course, because if thou gaze long into an abyss, as Nietzsche once said, the abyss may also gaze into thee. Have we the courage? Will our readers have the courage to stay with us on this perilous and uncertain journey?

My invitation to you is not, of course, arbitrary. It seems to me that you are amongst a very small group of thinkers today who have already started the process of speaking ‘without filters’. I’ve seen you deliver lectures to your students saying things that most academics would not dare even to think, let alone say out loud in public. I’ve read articles of yours that manifest the uncompromised honesty that I hope will inform, perhaps even inspire, this dialogue. One of the articles to which I refer, and which now entitles this book, is called ‘This Civilisation is Finished.’ Let that bold and unsettling statement initiate our conversation. No doubt it will require some unpacking. What did you mean when you declared that this civilisation is finished?

Rupert Read (RR): Thanks Sam. It is a privilege, in at least two ways, to be able to conduct this dialogue with you. First, it’s a privilege to be in dialogue on this vital matter with you, whose work on degrowth and voluntary simplicity is, in my opinion, simply the best there is. But I also mean that it’s a privilege, a wonderful luxury, to be able to have this conversation at all, because it is quite possible that in a generation’s time, or possibly much less than that even, such conversations will be an unaffordable luxury.

It is quite possible that, although we are living at a time that is already nightmarish for many humans in many ways (let alone for non-human animals), we will come to look back on these times, if we are alive to look back on them at all, as extraordinarily privileged. Right now people such as you and me don’t have to spend much of our time scrabbling for food and water or looking over our shoulders worrying about being killed. So we have a responsibility to make the most of this privilege.

What I’ve just expressed will strike some readers as exaggerated for effect. It is not. It is simply an attempt to level with everyone; to take up your invitation, Sam, and join you in a space of uncompromised honesty. Environmentalists are often accused of being doom-mongers. I think that the accusation is largely false, because I think that almost all environmentalists incline in fact to a Pollyanna-ish stance of undue optimism. This might prompt an accusation of me being a fear-monger or alarmist. I’m not an alarmist. I’m raising the alarm. When there’s a fire raging – as is the case right now, as I write, across the UK and across the world including in forests that are our planetary lungs – then that’s what one needs to do. Raise the alarm. This elementary distinction – between being an alarmist and justifiably raising the alarm – is exactly the distinction that Winston Churchill drew, under similarly challenging (though actually less dangerous) conditions, in the 1930s.

If people are feeling paralysed right now, I think it is probably because they are stuck between false hopes. On the one hand, there is the delusive lure of optimism, the hope that there will be a techno-fix that will defuse the climate emergency while life more or less goes on as usual. This is, I believe, in a desperately-dangerous way keeping us from facing up to climate reality. On the other hand, there are dark fears that people mostly don’t voice and don’t confront. My message, far from being paralysing, is liberating. One is liberated from the illusory comfort – that deep down most of us already know is illusory – of eco-complacency. One is able at last to look one’s fears full in the face. One is able at last to see the things that the other half didn’t want to see. And then to be freer of constraint in how one acts.

One of the ideas in the work of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein that most deeply inspires me is that the really difficult problems in philosophy have nothing to do with cleverness or intellectual dexterity. What’s really difficult, rather, is to be willing to see or understand what one doesn’t want to. After years of denial, and years of desperate hope, I finally reached a point where it was no longer possible for me to not see and understand the fatality that is almost surely upon us.

I have come to the conclusion in the last few years that this civilisation is going down. It will not last. It cannot, because it shows almost no sign of taking the extreme climate crisis – let alone the broader ecological crisis – for what it is: a long global emergency, an existential threat. This industrial-growthist civilisation will not achieve the Paris climate accord goals; and that means that we will most likely see 3–4 degrees of global over-heat at a minimum, and that is not compatible with civilisation as we know it.

The stakes of course are very, very high, because the climate crisis puts the whole of what we know as civilisation at risk. By ‘this civilisation’ I mean the hegemonic civilisation of globalised capitalism – sometimes called ‘Empire’ – which today governs the vast majority of human life on Earth. Only some indigenous civilisations/societies and some peasant cultures lie outside it (although every day the integration deepens and expands). Even those societies and cultures may well be dragged down by Empire, as it fails, if it fells the very global ecosystem that is mother to us all. What I am saying, then, is that this civilisation will be transformed. As I see things, there are three broad possible futures that lie ahead:

(1) This civilisation could collapse utterly and terminally, as a result of climatic instability (leading for instance to catastrophic food shortages as a probable mechanism of collapse), or possibly sooner than that, through nuclear war, pandemic, or financial collapse leading to mass civil breakdown. Any of these are likely to be precipitated in part by ecological/climate instability, as Darfur and Syria were. Or

(2) This civilisation (we) will manage to seed a future successor-civilisation(s), as this one collapses. Or

(3) This civilisation will somehow manage to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly, in an unprecedented manner, in time to avert collapse.

The third option is by far the least likely, though the most desirable, simply because either of the other options will involve vast suffering and death on an unprecedented scale. In the case of (1), we are talking the extinction or near-extinction of humanity. In the case of (2) we are talking at minimum multiple megadeaths.

The second option is very difficult to envisage clearly, but is, I now believe, very likely. One of the reasons I have wanted to have this dialogue with you, Sam, is so that we can talk about how we can prepare the way for it. I think that there has been criminally little of that, to date. Virtually everyone in the broader environmental movement has been fixated on the third option, unwilling to consider anything less. I feel strongly now that that stance is no longer viable. And, encouragingly, I am not quite alone in that belief.

The first option might soon be as likely as the second. It leaves little to talk about.

Any of these three options will involve a transformation of such extreme magnitude that what emerges will no longer in any meaningful sense be this civilisation: the change will be the kind of extreme conceptual and existential magnitude that Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher of ‘paradigm-shifts’, calls ‘revolutionary’. Thus, one way or another, this civilisation is finished. It may well run in the air, suspended over the edge of a cliff, for a while longer. But it will then either crash to complete chaos and catastrophe (Option 1); or seed something radically different from itself from within its dying body (Option 2); or somehow get back to safety on the cliff-edge (Option 3). Managing to do that miraculous thing would involve such extraordinary and utterly unprecedented change, that what came back to safety would still no longer in any meaningful sense be this civilisation.

That, in short, is what I mean by saying that this civilisation is finished.

————–

The paperback is available here and the e-book is available on a ‘pay what you want’ basis here.

Let’s be completely honest and admit that it’s not just the civilisation that is finished but so is the biosphere as we know it .

When this civilisation unravels we will see 450 + nuclear power station meltdowns and over 1300 spent fuel pool fires aerosoling ionising radiation into the atmosphere and oceans.

Lets tell the truth at the edge of extinction.

https://kevinhester.live/2018/12/28/this-civilisation-is-finished-ruppert-reid-paul-ehrlich-and-jem-bendell/

Good afternoon Sam,

104 pages and not one reference to the REAL cause of the looming catastrophe, overpopulation! You could have at least made a glancing reference to the deleterious affects of billions of consumers striving to emulate their rich Western cousins. Until we can convince World Vision, Oxfam etc. that compulsory depot Provera shots are a condition of aid, you are shouting into the abyss. Perhaps the looming flu pandemic will achieve what needs to be done – reduce the world’s population back to sustainable levels.

In our book you will find the following passage from Rupert:

“How should our population be reduced so as to return to something within Earth’s carrying capacity? This demands a book in itself. I hope we can

all agree that it should start with voluntary non-reproduction: educating women, choosing to have fewer or no children, going on ‘birth strike’. And it is important to reduce the human population in rich countries too—because we are the ones who are plainly over-consuming.”

We recognise that population is a major contributor to the global predicament and it deserves more attention. In a short book we couldn’t address everything in detail. But your point is noted Wayne.

Thanks for releasing this collaborative conversation! I look forward to reading its pages 🙂

Regarding population and family planning, – this absolutely needs to be voluntary, and free access for all needs to be available. All the researsh shows that the more women have sexual decision making power, then they have small families.

One concern i do have regarding population is that fertility rates only go down when people see their children survive to adulthood. This is at risk in the clinate crisis we have, starting with areas of high heat and desertification such as the Sahel/Sahara.

Working to economically support organisations who have been grossly affected by Trumps ban international spend on reproductive health is a good place to start.

Also I wanted to add that overpopulation has happened not because people are having bigger families, but that more and more mum’s and infants are surviving childbirth and the firat five years of life. Life expectancy has also increased significantly. I think we need to recognise that our past ecological balance with the earth in this sense was pretty brutal.

Another person who has an understanding of the very nature of the human predicament — but with a more optimistic outlook — is University of Minnesota professor, Dr. Nate Hagens. Using a systems synthesis approach to arrive at a big-picture description of the issues facing human society, Hagens asserts that climate change is just a ‘symptom’ of a “bigger picture.” The bigger picture, he says, reveals a very different story about our predicament – “one that integrates human behaviour, energy, and money into this superorganism, emergent dynamic of how humans are currently functioning.” Globally, humans are turning into an energy-squandering superorganism, like some blind, purposeless amoeba.

Moreover, in his recent Earth Day talk, Hagens mentions that he has been meeting with US policymakers, governors, mayors, corporate CEOs, and other politicians, and “found something amazing.” — Once they put on the hat that goes with their official role, they can only see more economic growth as an essential part of a solution to climate change.

Under his framing, viewing humanity as a superorganism, Hagens declares four things that are NOT likely to happen – 1/ “We’re not likely to grow the economy AND mitigate the Sixth Mass Extinction and climate change; 2/ We’re not likely to grow the economy by getting rid of the bad fuels and replacing them with rebuildables [renewables that have to be rebuilt every 20-30 years]; 3/ We’re not likely to choose to leave fossil carbon in the ground because it’s so tethered to our experiences, our life standards, our wages, our profits, our growth, the cheap stuff that we buy; and 4/ Governments are not likely to embrace limits to growth before limits to growth are well past.”

A video of Hagens’ 46-minute Earth Day talk, along with a complete transcript, are available by following this shortlink – https://wp.me/pO0No-4Iz

Latest post from Frank White…The Great Simplification coming next decade with 30% drop in capitalist economies, says Dr. Nate Hagens

Thanks for your work, Samuel. Looking forward to reading it.

I just looked over the Table of Contents and notice parallels to my own (somewhat shorter) essay:

https://medium.com/@seamusohailin/pontoon-archipelago-e53f28fa6fae?source=friends_link&sk=c5103214eb9c1972fc2724708c8145a7

It is rare in my experience to read a book and agree with more than 90% of its content – this one comes close to the 100%.

Response to the population size comments – maybe worth reading “Empty Planet” by Darrel Bricker and John Ibbetson to gain better understanding of influences affecting population size and change.

That population growth is the real cause is difficult to accept. As a simple thought exercise, imagine selecting 5000 of the most wealthy people, the successful businessmen and placing them on an island with rich natural resources. Compare to what might have happened if 5000 of the most caring, socially aware and effective social enterprise initiators had been selected instead. Which scenarios would likely result in better managed resources, a peaceful safe and loving community?

In both cases its not the population nor size of island – its the appreciation of value of community rather than self.

In a world in which personal gain at any cost is valued above community then it should be no surprise that planet and other life is treated the same. I suggest this is the fundamental cause.

The choice is simple the former scenario is based on fear the latter scenario is based on love. Now there are two words greatly misunderstood, fear found at the seat of most large groups of people which we call Nations etc, Love, found in small groups which we call families.

Visualize a future shaped by a pandemic that within a very short time reduces the human population by 5 billion or so. This would get us to Option 2 rather quickly, I would think.

“When I look at the world today, I see the vast majority of academics, scientists, activists, and politicians ‘self-censoring’ their own work and ideas, in order to share views that are socially, politically, or even personally palatable.”

One of the reasons why the population issue is often avoided is because it can be a rather sensitive subject, one of the reasons being that population growth is higher on some continents and in some countries than others. Moreover, immigration also affects population growth on some continents and in some countries more than others. Pointing the above out could be misconstrued.

Another important factor is that economic growth and population growth are integrated. Should populations drastically reduce, economies would shrink. One of the reason for immigration schemes existing in many nations is for replenishing local populations and for adding to the skilled and unskilled workforce where necessary. During elections voters always vote for parties that promise economic growth that would lead to more prosperity for all. Green parties hardly ever get into power.

With there being so many holy cows and taboos (the above just being a couple) it is difficult to move the debate forward. The biggest elephant in the room of course is that in terms of climate change, very few activists are prepared to give up their cars (that would include climate scientists) to save the planet.

I have discussed some of these issues in my latest essay, “There are no limits to growth”.

I look forward to reading ‘This Civilisation is Finished’.

Latest post from JJ Montagnier…(6) There Are No Limits To Growth

Regarding whether there are limits to growth or not, see this new essay by Hickel and Kallis: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59bc0e610abd04bd1e067ccc/t/5cbdc638b208fc1c56f785a7/1555940922601/Hickel+and+Kallis+-+Is+Green+Growth+Possible.pdf

Conclusions from Hickel and Kallis call for a review of what it means to be sustainable. The idea that PV and batteries, Electric Vehicles and the like are steps towards sustainability can only be tested in a scenario where the availability of anything other than knowledge and experience is available. In other words, if extraction, manufacturing and production in the current system was to cease, how long would an ‘island of sustainability’ last?

The movement of eco-villages, transition towns and self sufficient communities seems, by and large, to conveniently forget that replacement, maintenance and repair of so called sustainable systems remains dependent upon current non-sustainable systems. The challenges are fascinating when the target is taken seriously.

I had in mind to kick off the first phases of a research project based on this

https://www.researchgate.net/project/The-real-value-of-human-knowledge

Just outlining ideas now, would greatly appreciate some input

What a promising conversation. Thanks, all!